Occupational asthma

Asthma is 'work-related' when there is an association between symptoms and work. The different types of work-related asthma should be distinguished, since the implications to the worker and the occupational health management of the disease differ

Work-related asthma includes two distinct categories:

- work aggravated asthma, i.e. pre-existing or coincidental new onset adult asthma which is made worse by non-specific factors in the workplace, and

- occupational asthma i.e. adult asthma caused by workplace exposure and not by factors outside of the workplace. Occupational asthma can occur in workers with or without prior asthma

- occupational asthma can be further subdivided into:

- sensitiser-induced occupational asthmacharacterised by a latency period between first exposure to a respiratory sensitiser at work and the development of immunologically-mediated symptoms

- irritant-induced occupational asthma that occurs typically within a few hours of a high concentration exposure to an irritant gas, fume or vapour at work (1)

- workplace agents that induce asthma through an allergic mechanism can be broadly divided into those of high and low molecular weight

- the former are usually proteins and appear to act through a type I, IgE associated hypersensitivity.

- some low molecular weight chemicals are associated with the development of specific IgE antibodies, this is not the case for the majority

- almost 90% of cases of occupational asthma are of the allergic type

Occupational factors account for about 1 in 10 cases of asthma in adults of working age (4)

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) estimate that 1,500 to 3,000 people develop occupational asthma each year. This rises to 7,000 cases a year if work-aggravated asthma is included

- it is thought that thereported incidence of occupational asthma is underestimated by about 50% (3)

- it is the commonest industrial lung disease in the developed world with over 400 reported causes (2)

- most frequently reported agents include isocyanates, flour and grain dust, colophony and fluxes, latex, animals, aldehydes and wood dust

- workers most commonly reported to surveillance schemes of occupational asthma include paint sprayers, bakers and pastry makers, nurses, chemical workers, animal handlers, welders, food processing and timber workers

- high risk work includes (2)

- baking

- pastry making

- spray painting

- laboratory animal work

- healthcare

- dentalcare

- food processing

- welding

- soldering

- metalwork

- woodwork

- chemical processing

- textile, plastics and rubber manufacture

- farming and other jobs with exposure to dusts and fumes

- smoking has been identified to increase the risk of occupational asthma in workers exposed to: isocyanates, platinum salts, salmon and snow crab

Occupational rhinitis and occupational asthma frequently occur as co-morbid conditions (1)

- epidemiological evidence from the general population of a strong association between the development of asthma and a previous history of either allergic or perennial rhinitis. Occupational rhinitis is purported to be a risk factor for the development of occupational asthma, especially for high-molecular-weight sensitisers

- rhino-conjunctivitis is more likely to appear before the onset of IgE associated occupational asthma

- risk of developing occupational asthma is highest in the year after the onset of occupational rhinitis

Diagnosis of occupational asthma

- occupational asthma should be suspected in all workers with symptoms of airflow limitations (2)

- the following screening questions could be useful in patients with airflow obstructions:

- are you better on days away from work?

- are you better on holiday?

- patients with a positive answer should be considered as having occupational asthma and should be investigated (2)

- made most easily before exposures or treatments are modified

- serial measurement of peak expiratory flow is the most available initial investigation

- minimum standards for diagnostic sensitivity >70% and specificity >85% are:

- at least three days in each consecutive work period

- at least three series of consecutive days at work with three periods away from work (usually about three weeks)

- at least four evenly spaced readings per day (2)

- when done and interpreted to validated standards there are very few false positive results, but about 20% are false negatives

- skin prick tests or blood tests for specific IgE are available for most high molecular weight allergens, and a few low molecular weight agents but there are few standardised allergens commercially available which limits their use. A positive test denotes sensitisation, which can occur with or without disease

- the diagnosis of occupational asthma can usually be made without specific bronchial provocation testing, considered to be the gold standard diagnostic test

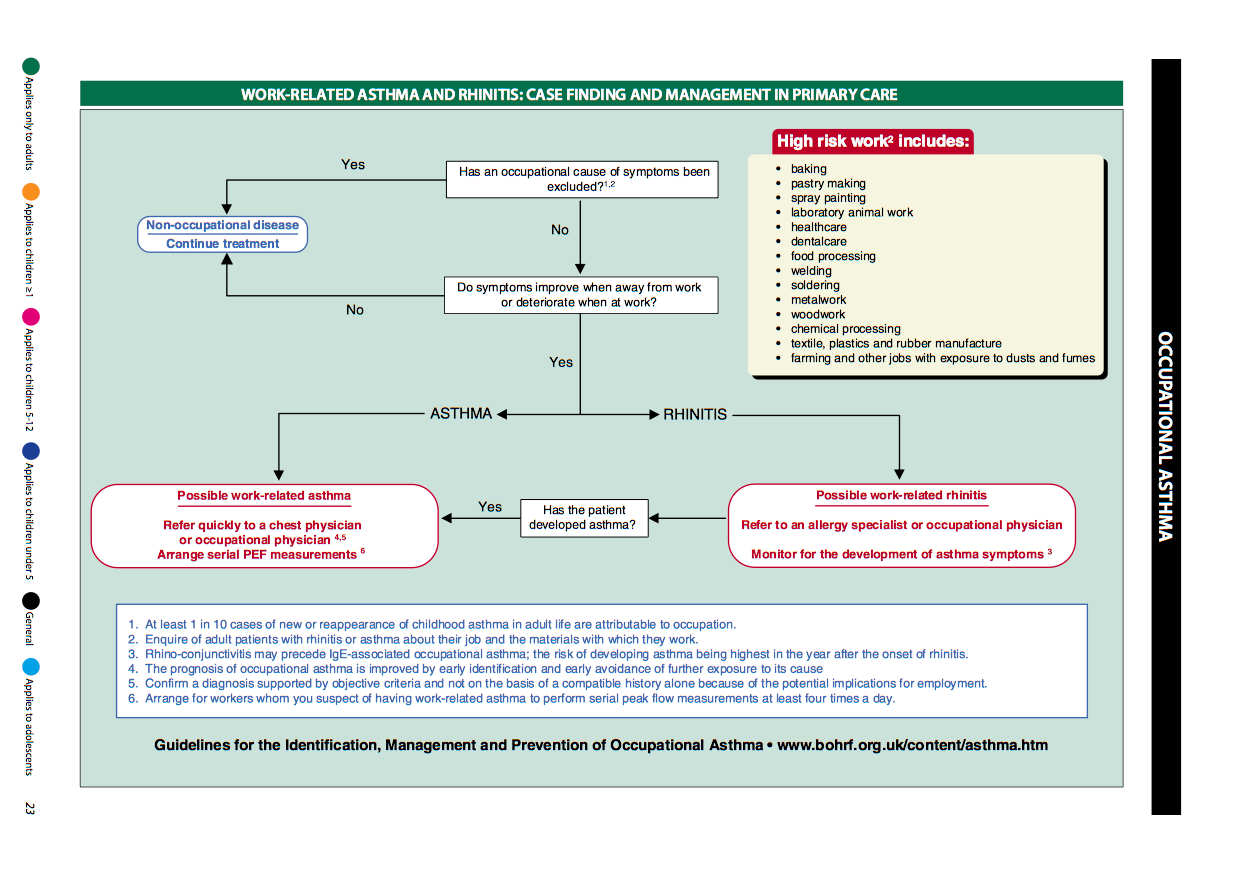

Work-related asthma and rhinitis: case finding and management in primary care (4):

1 in 10 recurrences of asthma in adults are due to occupational asthma, so take a detailed history if important. If a patient has rhinitis which is worsened by being at work, they have a higher risk of asthma starting in the 1st year of symptoms. Occupational asthma has a worse prognosis if there is continued exposure, so prompt diagnosis is important. Advise serial PEF readings (at least 4 a day) and prompt referral to a respiratory specialist. The following chart is helpful:

management principles:

- primary prevention aims to prevent the onset of disease, often by reducing or eliminating exposure to the agent in the workplace

- is the most effective measure

- relocation away from exposure should occur as soon as diagnosis is confirmed, and ideally within 12 months of the first work-related symptoms of asthma (2)

- reduction in airborne exposure will result in a reduction the number of workers who become sensitised and who develop occupational asthma (1)

- secondary prevention aims to detect disease at an early or presymptomatic stage for example by health surveillance

- tertiary prevention aims to prevent worsening symptoms by early recognition and early removal from exposure and is considered later under the management of an identified case of occupational asthma

- referral from primary care:

- if possible work-related asthma

- refer quickly to a chest physician or occupational physician

- arrange serial PEF measurements

- if possible work-related rhinitis

- refer to an allergy specialist or occupational physician

- monitor for the development of asthma symptom

For more information then consult the British Occupational Health Research Foundation http://www.bohrf.org.uk/

Reference:

- (1) Guidelines for the prevention, identification & management of occupational asthma: Evidence review & recommendations. British Occupational Health Research Foundation. London. 2010

- (2) British Thoracic Society (BTS)/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 2011. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. A national clinical guideline

- (3) Fishwick D et al. Standards of care for occupational asthma. Thorax. 2008;63(3):240-50.

- (4) NICE (November 2024). Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management (BTS, NICE, SIGN)

Related pages

Create an account to add page annotations

Annotations allow you to add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation. E.g. a website or number. This information will always show when you visit this page.